I've decided to put this page together because on looking around the internet I see heaps of rubbish, mis-information and myth out there for people who are on

as an anticoagulant.

Firstly - the good news

I wanted to say that

managing my INR myself is incredibly simple and

takes me about 5 minutes per week. Learning to use an INR monitoring machine is dead simple (a quick video provided) and (almost) any idiot can do it. If you buy strips online they cost so little that if you are an able bodied person you just couldn't consider doing it any other way.

By using the Coaguchek XS I have been essentially

free to travel as I wish (moved from Australia for a year in Finland, traveled to the UK and other places) and

more or less unbound in any way by being on anticoagulants.

As a bonus its

been really cheap, with tests costing me less than $6 per test.

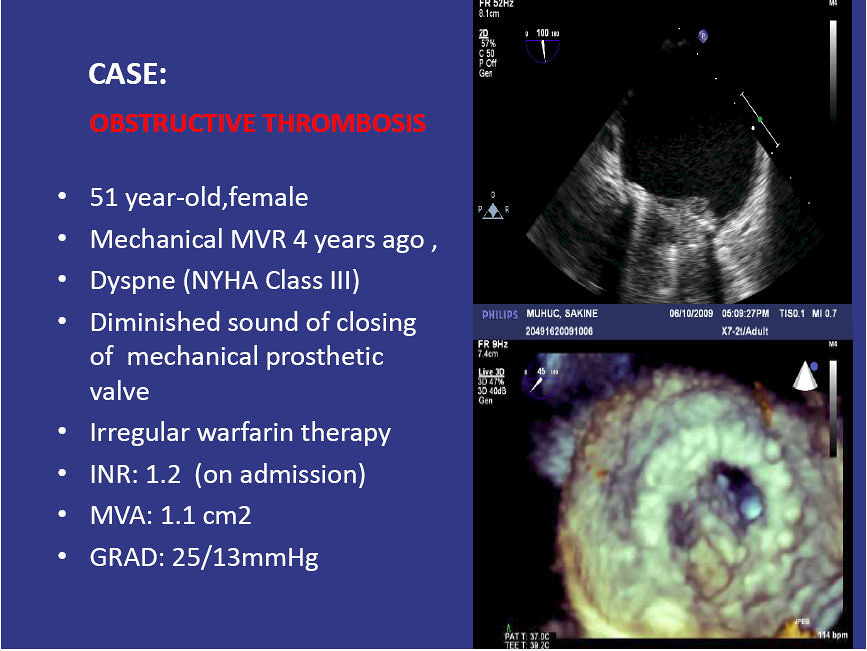

In this post my main focus is on those of us who are on anti-coagulants for the fact that we have a mechanical heart valve. As I understand it there are quite a few out there who simply do not monitor their INR after their heart valve replacement, and perhaps bumble along with a fixed dose and no idea if its good or bad.

So my Valve Brothers and Sisters if you are still reading its all good news. I encourage you to go to eBay and buy a Coaguchek XS (

or simmilar) get online for strips and look after your health, for your self by yourself!

In a nut shell what I do is:

- sample my blood to determine my INR

- write that down (spread sheet, but book works)

- determine if its been over time falling or rising (a graph on a SS really helps)

- make a small adjustment to my dose if needed to correct for my INR falling or rising (usually adjustment isn't needed and its better to leave it alone, more later)

That's it ...

compared to a diabetic, life on warfarin is really simple.

Looking at the research, by following good practices (simple really) you can make life on warfarin much safer than the stats that are usually presented. Point of Care machines (like my Coaguchek) make dosing warfarin both accurate and convenient.

The rest of this post is really just here to explain more details and provide a basis for my view.

In this post I will refer to

warfarin as the name of the chemical substance we take. So for those (Americans usually) who can only think in terms of product names and refer to this as

Coumadin (which is actually a product name of one company) you can be clear that I am not talking about any product in particular. Calling it coumadin all the time is

like saying you have a Hover instead of saying you have a vacuum cleaner when you actually own an Electrolux. I use the product called Marevan , but its unimportant to the discussion.

I thought I should also say up front that my view is that :

Everything I know is subject to change based on more information. The more I learn the more I tune what I understand and how I see what I know as meaning.

I have my INR target determined by my condition, which is that I have a modern pyrolytic carbon mechanical valve. If you have other reasons for being on anticoagulants then consult with your physician as to what your target INR is and then apply that to the information below.

So, why is this here?

Essentially I was a annoyed with my INR monitoring clinic. I saw that it was essential for me to have started with them however I out grew wanting to be managed for reasons such as:

- I didn't want to be fronting up for a vein blood draw fortnightly, often weekly and sometimes twice a week. It was inconvenient (as I have to go to work) and uncomfortable (as sometimes they had trouble getting blood)

- I wanted the absolute best for my health, and I became certain that only I was sufficiently motivated about things to ensure that

- I learned enough to realize I could do it better than the clinic and for less money and for less hassle

I believe strongly that for those of us who are on warfarin for no other reason than because we have a mechanical valve, life really can be safer than if you took the tissue option to avoid what the doctors drummed up as the horror of anticoagulation therapy.

So, lets next have a ...

Quick summary

This post assumes you are already on warfarin and have been for some months. I also assume that you are not one of the small percentage of people who are having difficulties with it or having compounding problems with being on other drugs. I hope that after reading this you can stabilise your dose and stabilise your INR and reduce any possible complications ...

So this in this post I say:

- keep your doses steady, by this I mean take the same number mg per day. I feel there is evidence to support that alternating high / low doses lead to increasing instability

- there is a natural swing in range of INR which will occur even with the same dose. Accept this and don't try to micro-manage it

- I have learned that nothing is fool proof because the simpler you make things the more you encourage people to be stupid. So if you can't do maths or work with numbers (like what's half of 5 + 5) and are currently with an INR management clinic, then stay with the clinic (even if you're unhappy) and just bitch about the mistakes they make (and the frustration they cause). Be comfortable in the knowledge that you'll make worse ones if you manage yourself and can't do numbers yourself.

- measure your INR consistently, getting a good sample helps (I show a video of a method I use) as does consistency of technique.

- there are many myths about INR which lead you to make wrong assumptions (and I attempt to demonstrate this with some facts), these myths perpetuate due to simplifications (aka dumbing down) and extrapolations from those simplifications.

- measure frequently (like weekly or fortnightly)

- if there is a trend which worries you, measure more often (such as again in a 3 days) to see if the trend is continuing or returning of its own accord (it may well just do that)

- adjust doses in small amounts, such as 0.5mg per day.

- split pills not average irregular doses

- don't think in weekly doses, think in daily doses

If some of these points seem serious - well that's because this is a serious matter. You can do yourself harm with this if you are not careful. Equally if you are on anticoagulants and are testing infrequently (I've heard of people testing every few months!!) you can do harm too, so go get a machine ASAP and start taking better care of yourself.

What is INR anyway?

Well INR stands for International Normalized Ratio. Wikipedia has a good summary

here. Reading that one can see it boils down to a ratio (you know, like 1 over 2 is a

ratio) with

my clotting time (which will be longer)

over the

"normal" clotting time. This is of course slightly crazy as what is a "normal clotting time" ... would there not be variation in times among people?

The answer is of course

yes (

and the details are there to be found for anyone who is interested enough to read). But for people uninterested in details I bring this up because I wish to stress a significant point:

THIS IS NOT AN EXACT SCIENCE AND THERE ARE RUBBERY EDGES TO EVERY ASPECT OF IT - SO DO NOT FRET OR OBSESS ABOUT FRACTIONS OF DECIMAL POINT.

Ok, with that (important) point out of the way lets move on... Clearly the first point in working out your INR is...

Getting Blood

Perhaps obviously when managing your INR one of the first things you need to do is get blood, to see how fast it clots. There are more or less two ways:

- the labs (which means you aren't managing your INR) use a needle and a syringe. Personally I'm no fan of "the jab" as I've had more than my fair share over (most of) my life and also only have an easy vein on my left arm. This results in frequent annoyance.

- a (finger) pin prick and use of a Point Of Care machine. This is actually becoming more common (even in hospitals) in the medical world as people begin to grasp that the devices are both sufficiently accurate and cost effective to run

Naturally I use the finger pin prick POC device, as the idea of stabbing myself with a longer needle and sucking blood is not appealing.

So when doing this you need to follow the instructions of the device. I happen to use a Roche Coaguchek XS and it specifies 8µL or "a full haning drop". Actually getting enough blood is often not as easy as it sounds. Sure you can just give yourself a good scratch and get it, but if you do this frequently (

I'll get onto that in a minute) its annoying to have what amounts to a permanent small injury on one of your fingers.

So, firstly on some mornings (

I happen to test on Saturday mornings as my routine) I sometimes had trouble getting a good blood sample and would get the annoying "

Error 5" displayed. This means you didn't get enough blood into the test strip and you'll have to toss the strip and try again. At $5 a hit its a slightly annoying thing to have happen ... it gets more annoying when you've blown two strips to finally get a reading with the third (meaning you've just cost $15 to check your INR).

My method is to lightly wrap a small rubber band (

which I've cut to make it a small rubber strap) around my finger to act as a pressure bandage and to restrict the blood flow back up the vascular system. This means I can regularly get a reliable sized blood sample and (perhaps importantly) stay within the strict guidelines of Roche on the maximum permissible time that can pass between lancing and application (

supposed to be 15 seconds, which I think is actually baseless, but that's a different post). From the Roche Coagucheck manual...

So now you know if you didn't before ...

Anyway my sample method is described in this video:

So as you can see, my method assures that:

- that you get more than enough for a good sample (and to avoid Error 5 and wasting a strip)

- do everything consistently and repeatably

- avoid milking the finger excessively (something mentioned in the manual as a no no)

- minimise the lance injury (who likes ongoing discomfort?)

- follow the 15 second rule (and preferably keep time between "ready beep" and application of blood consistent too)

Indeed using this system the

time from starting my pressure bandage (and remember, you're not aiming to cut your finger off, just restrict blood flow, so don't wind that band on too tight)

to getting a sample on the strip is

repeatably less than 15 seconds. Which of course means that there is minimal time for anything metabolic to occur.

Finally I would encourage everyone who is starting out taking their own INR to compare their results to a lab draw (

and please, do keep which lab you go to consistent, as there is significant interlab variation). If you compare your samples to a lab make sure you always follow the same procedure, as variations of your procedure may also influence your results. When I first started I was often up to 0.8 units away from my lab. Once I'd standardised my approach I was down to less then 0.3 (which is not significant really).

Sidebar: a quick comment about lancing, always lance the side. There are a few reasons for the choosing the side:

- ask a diabetic, over time pricking the same place you damage the nerves, doing the side minimises the effect of that

- it hurts less

- the skin is thinner and so the lance does not need to be as deep

- if you need to do work later it won't be as annoying there as a finger tip

So using the methods above you can get good consistent readings of your INR and not waste strips. Which then brings us on to the way that you achieve your target INR, that is...

Dosing

In this post I will assume that

you are already started on warfarin and have something like a stable dose (

I'll discuss stable in a tic).

Starting warfarin is a critical time and frequent monitoring needs to take place to ensure no problems arise and to work out your sensitivity to warfarin. Actually blood tests exist for this, and are helpful in identifying thegenes of those who need significantly lower doses. To my knowledge this is seldom done. However I digress.

Being stable on warfarin essentially means that you have an INR somewhere between 1.9 and 4, even if that wanders around from time to time. I hope that by reading this post that you may be able to make some changes to how you do things and your INR fluctuations may actually reduce. In my view it would seem that to some extent achieving INR stability is made more exasperating by those who manage INR. I will present here some of what I've found and hope that it helps you.

Essentially I dose myself these days, but some people may just do their own testing, and call that into a lab or clinic who manages your dose for your (aka: tells you what to do). Personally I've found that to be a headache, although less so than when they were drawing blood

and managing my INR. The reasons for this are many fold; everything from the hassle of getting in during hours I needed to be working, weird dosing advice through to overzealous micro-management of my dose and attempting to steer it.

At the end of the day you really just don't know who's at the clinic, who's keeping track of your data, what their view of this is, what dosing strategy they use, if they know diddley about it. To this end I took over my own dosing about a year after getting my mechanical Aortic valve. To be honest since then I've learned heaps and my INR is much more stable.

NOTE: I believe that if you are going to do your own dosing then you must be of the mindset to be competent to do so, be rigorous in what you do and be willing to take responsibility for yourself. If you do not feel this way, then I strongly recommend you stay under someone elses care and be a passive recipient. To me this equates to being a victim instead of in control.

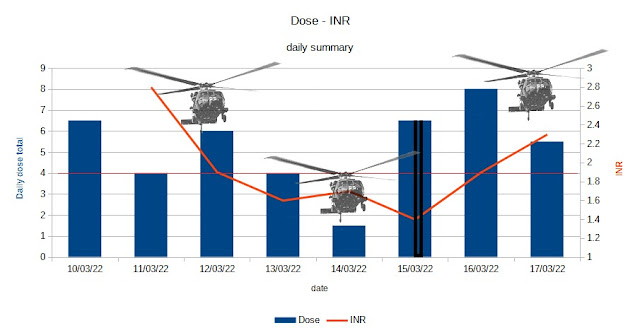

So first let me present my 2013 data and I'll use that to discuss a few points. Note that each data point represents one week. If I was testing monthly (or bi-monthly as some do) I would not even see these variations. So while extra data helps to see things its important to not over react to it.

On this chart I have my INR (in blue, with the values in blue on the LHS) and my dose in mg of warfarin. There is also a red "moving average" of my INR in there too which I'll explain in a moment.

I guess that you'll perhaps see that its not "rock steady", however it sits nicely within a range of (for that period) no more than 3.4 and no less than 1.9 ... this is a pretty good range actually. This result gives me:

- an average of 2.5

- a standard deviation of 0.3

- and a score of 91% of being inside my range

91% inside range is better than most clinics obtain.

I think its important to point out the language used by clinics and the misunderstanding of that by the public: when the clinics say "stable INR" they don't mean flatline (only dead people have totally steady metabolisms), essentially nobody has a "stable" INR. Rather people have INR's which will remain within a range for a given dose. Please refer to my page "

the Goldilocks Dose" for a discussion of mine.

As you can see, I do make small changes to my dose, but only when I see that it is trending up or trending down.

This is the reason for my having that moving average: it helps me to see this trend (

in conjunction with looking at the raw data graph too).

This change in trend indicates a shift in metabolism (

perhaps caused by diet, perhaps by health ... it doesn't matter),

and you can then re-position your dose by a small amount to optimize your outcome.

Some important points emerge from a closer look at the graph too. For instance in the earlier part of the year I was in hospital to have some surgery, there they managed my dose and took me off warfarin for a few days for the surgery. You can see that my dose went down substantially (soon to be followed by my INR). I increased my dose (from 6 to 7mg) and my INR responded rapidly. It fell a little and I thought I should increase my dose by much less at this point) and it rose again.

Anyway, you can see the see saw effect happening, frequent dose changes, rapid and significant INR swings. From this I could see the significance of small changes in my dose and developed the view that:

make dose changes small.

From then on you can see that my dose changes were small, in the order of ¼ a mg per day (

yes, that's right I was splitting a 1mg tablet into 4 and putting that with my 7.5mg to make it 7.75mg per day). As to why I go to such lengths of consistency is because

I believe that consistency is key to this.

myths

I find it interesting that people believe ideas which are mutually inconsistent. For example:

- INR takes days to show the effect of a dose change

- skipping a dose will be a big problem (and why would that be if INR takes days to be effected?)

- you can work out a weekly average dose and then divide your tablets across that (so 10mg one day, 5mg the next, or something like that)

Now let me say that I am not going to flatout disagree with these,

but to make clear that they are simplifications. Simplifications have a role to play in our lives, from making communication clearer through to helping us make sense of the complicated.

They should not be used to make decisions or predictions.

So it is in making dose adjustments using these simplifications as a basis where we cause problems

Now (

being an engineer and a biochemist based science trained person) I naturally wanted to understand if there was anything that could assist me to model my INR and make predictions.

That is after all why science has got us to where we are rather than witch-craft or entrail gazing. As I had been observing my data (

gathered from weekly testing) I was of the view that some patterns were emerging. What I needed next was some good experimental data...

Experimental Data

Lets look at a some data that I actually took just before I went into hospital. I knew that I was going to be off warfarin for a few days during my stay (turned out that I was off warfarin for 3 days), so it provided a good opportunity to use myself as an experiment. I like graphs, as they are a really handy way to represent numbers.

If you are at a point in your life where you can't manage numbers or understand them then I urge you to not manage your own INR.

My actual measured INR had a gap in it because (

variously) I was in surgery, then in ICU then unable to get my hands on the data from the hospital. So I do not have a reading for some days, thus you will find a discontinuity of the

Measured INR. The

green line was what I initially developed for my rudimentary mathematical model of how INR

may behave.

The model of INR was based on nothing more than knowledge of the half life of warfarin in the body and applying general principles to it. It is not based on measurements actually got from me (which would be bloody nice to have mind you). In general warfarin is removed by our bodies at such a rate that half of what was put in is removed over 2 days: that is to say it has a half life of about 2 days. Obviously each person is different (based on well known genetic parameters actually) and each person will have variation depending on a number of factors (health, other drugs ...). Since you take an amount of the drug every day your level of warfarin in your system is a combination of what you just took, what was left over from yesterday, the day before and so on ... so for a 7mg dose this would be something like:

7.00, then 12.25, then 15.75, then 17.85 and stabilising at 19.60

Then I've simply applied a fixed scalar multiplier to the accumulated amount. This is of course assuming that the INR response to warfarin is linear (which perhaps in part of the curve it will be). So its a rubbery model, but better than nothing.

Looking at the graph you can see that green line sank to an INR of barely above 0.5 (

which is probably illogical as it will not make my blood clot faster, although that's an interesting question in itself), however (

of course) the trend line didn't sink as far (

sinking to an INR of 1). I have found that the moving average is a helpful tool as it essentially adds simple buffering to the system (

which it may in practice have).

When both my dose and then testing did resume the INR which was measured was actually quite close to the model, somewhere between the Moving Average and the Predicted INR. That it did not rise as fast as the others did, could be attributed to (

for instance) a lack of responce to the 1mg increase in dose for two days. None the less it was continuing to rise where the model plateaued out.

This makes it clear that

my INR dropped rapidly upon stopping the dose (

which would seem obvious)

which counters the "myth" that it takes days to see any change in the INR. Its a real pitty I didn't have opportunity to measure it for the whole time. For obvious reasons I'm unwilling to go off for 3 days just for data gathering. (

I know, I know, where's the commitment...)

Subsequently to this I've missed a dose by accident (

and more than once I may add) and have then taken readings to see what has happened. My (

sorry to say) many observations of missing a dose and taking taking daily INR readings have shown that

the response of INR to change in my warfarin level is surprisingly rapid.

Thus further nailing down the coffin lid of "it takes days to see any change".

So lets examine the "

alternating dose" strategy briefly in this light. As we've seen INR does vary somewhat even day by day it can be observed. People look at their calendar or pill boxes (a physical version of a calendar BTW) and think, "oh well I'll just alternate my does 10mg and 7.5 mg" (I assume such alternation is because in the USA Coumadin is commonly found in doses which includ 7.5mg and 10mg

This makes sense because medical people know that most of the general public can't be trusted with numbers (

return again to my advise above for the numerically challenged) and so basic arithmetic is out of the question. Combined with the fact that few people want to have more than 2 pill sized on hand and are likely to get them confused anyway (

again, I refer to my numeric advise above).

They would think that their strategy of alternating doses of 10 and 7.5mg would give a value of 8.75mg per day on average ... sadly it doesn't, but I'll get to that.

So taking this alternating dose you will likely see warfarin values (and hence probably INR values) following something like the pattern in my simple mathematical model

Which shows an average dose of

8.75 *(the orange linear trendline) and an INR potential varying between 3.4 and 3.6 ... so think kid bouncing up and down on a trampoline ... you know, simple

harmonic motion.

However firstly its not that simple because you probably are taking your 10mg dose on Sunday and Saturday as shown in the above graph ... of course we all know that the weeks run into each other, so that means that on Monday you've really had the dose of 10 and 10 added ... so it will actually look like this:

Notice that now after Sunday we've got a significant extra bump in it? The modelled INR line now looks far less even doesn't it...

In fact the average is

now 9 not 8.75 when we consider the entire period and the overlap of the weekly roll around from Saturday to Sunday ... To do proper alternating dose you'll need to switch your starting day in your pill box from 7.5 to 10 each week, and remember that ... suddenly its not as simple as it sounds and just keeping it "steady as she goes" with a daily dose which is the same or very close to it is looking better. ... if you can add up and divide.

I'd also say this makes the

other myth of taking irregular doses and averaging across the week will be OK to be another bad idea, probably based on a simplification that the response to INR is not seen within a week.

Sure, if you really want to do it then fine, however if you have occasional high spikes of INR and a bleed event don't say I didn't give you the reasons for that.

Going back for a minute to my earlier (weekly sample) years chart we

can see how on occasions small dose changes occasionally resulted in

rather large spikes in my measured INR? I have the view (and I've been working on the data to support this view for some time now) that such is caused by the addition of other metabolic influences which combine to push INR high. The more things that are influences the more that the situation could occur that the INR be flung even higher due to a synergy of events.

Simple harmonic motion is just up and down, but when you add another influence things get difficult to predict.

Try bouncing on a trampoline with someone else. Simple harmonic motion becomes more complex.

You may not bounce as high, or you may be flung off.

You may not think that the bounce in INR is created by the bounce in the residual levels but I see evidence that it is. I've discussed above, with a number of pathologists and even endocrinologists. However despite this I have read some idiots (

clinics) giving instructions to patients for even greater variance over even greater spacings: such as alternating doses of 7 and 12 or 10mg twice a week and 6mg the other days.

God only knows what will be the outcome of that one but I doubt it's stability.

As I pointed out in my other post (see post

The Goldilocks Dose),

I have found that even on a

dead steady dose my body has variations (bounces or oscillations) in INR even when I have a continuous regular daily dose:

| dose mg |

7 |

7.5 |

8 |

8.4 |

| MAX INR |

3.19 |

3.14 |

3.64 |

3.87 |

| Average INR |

2.43 |

2.60 |

2.77 |

2.95 |

| MIN INR |

1.82 |

1.95 |

2.08 |

2.21 |

So if someone was attempting to micro manage the INR which was falling or rising based on some other cycles (

and look again at the graph above to see the times when there was variation but no dose change)

it could make you even more unstable. Keep a steady hand on the tiller.

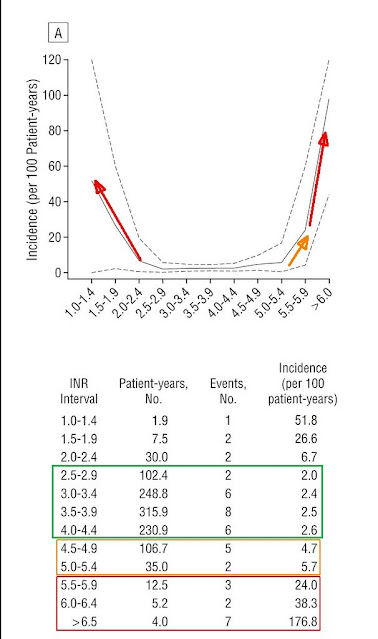

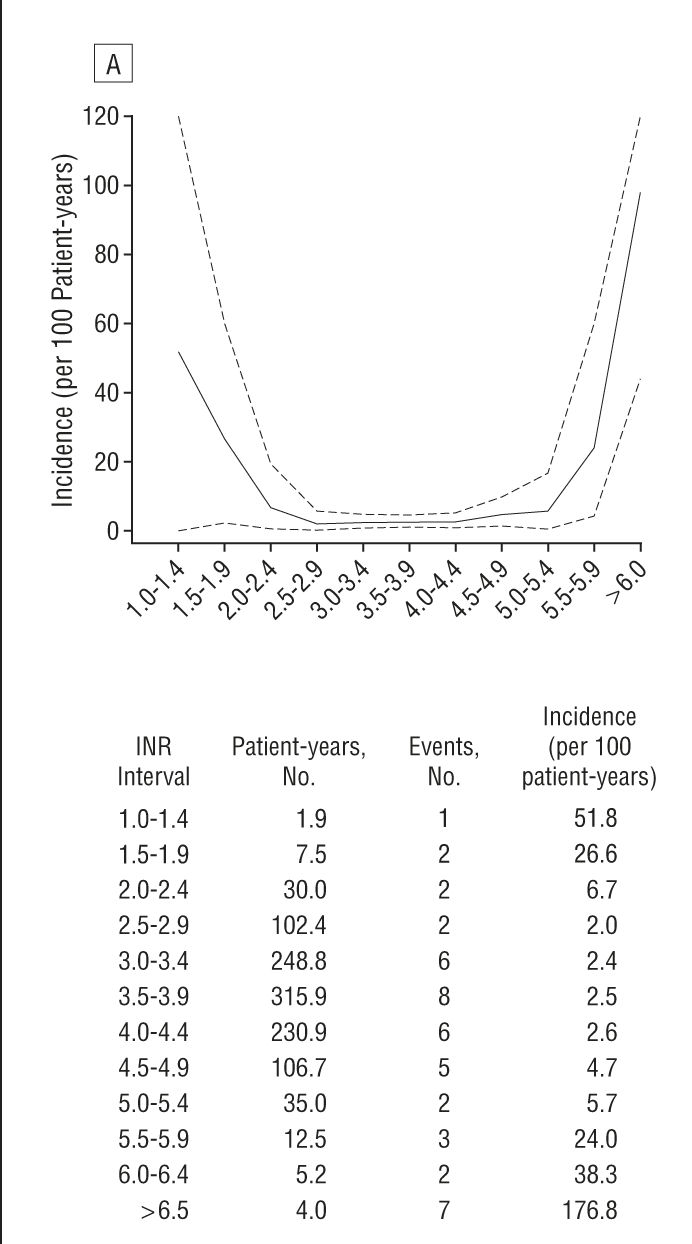

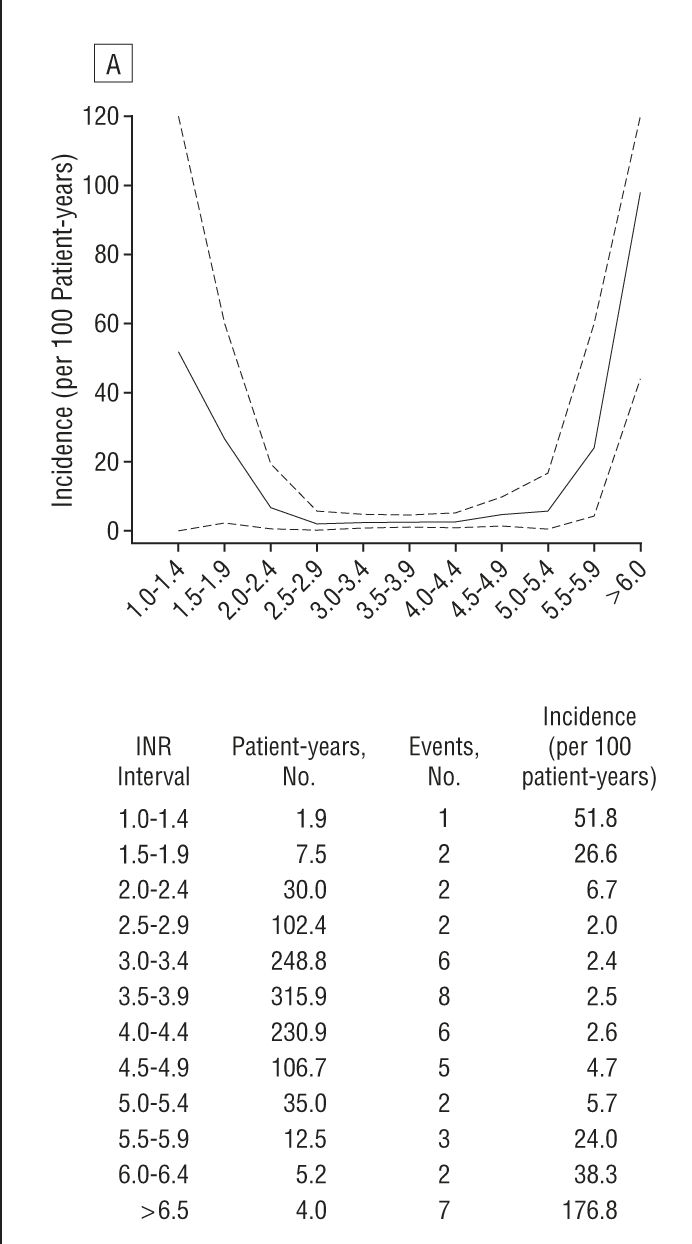

When it comes to INR range and the health issues with being too low or too high, a great resource is a study which has covered some thousands of patients and documented INR and "events". The important chart (for those of us with mechanical Aortic valves) is this one (

article here)

Which shows that

between 2.0 and 3.5 the number of "events" (you know, bleeds, thrombosis ... the usual stuff)

is really low. Either side of that and the numbers step up. This feeds into my strategy, helping me set my bounds. Interestingly my surgeon initially recommended a range of 2.2 ~ 3 ... which sits well with the above findings...

my strategy

I aim for a target of 2.5 (

which btw is the recommendation of the European Society of Cardiology for a mechanical Aortic valve, if you have a different valve you should follow the recommendations for your valve). I try to keep my variations in INR small, but know that fiddling will likely set up see saw events (making things wose). Thus I only alter dose if things are trending out of range. As I mentioned my average is 2.5 (bang on target) and my standard deviation is 0.3 ... which means that mostly I'm somewhere between 2.2 and 2.8 (if you didn't know what a

standard deviation is).

So now that I have set you up with much of my reasoning, I can say that basically my strategy is this:

- keep the doses regular (same dose each day)

- do not adjust dose unless you see a consistent trend down to a minimum bounds

- even then stay your hand till you know more. (I increase measurement to twice per week, this allows me to see if its sinking more still or rebounding to within bounds again)

I normally measure weekly and when I see my INR going out of bounds I do what I call an "ad hoc" measurement where I measure again on Wednesday (

recalling that I measure on Saturday). This gives me the extra information to see if INR is still going low/high or has stabilised (and thus likely to return on its own).

I know that dose adjustments can set up see saw responces, so I try to alter my dose infrequently. You can see it sitting at the same level for weeks at a time in the graph above, with often only 0.25mg variations when I do change it.

I encourage you to (

after reading this) again read my post on

The Goldilocks Dose and review this in the light of the above some of the points I made in there.

I think these two article go hand in glove, but can't work out which should be first. Specifically the points about cycles which seem to occur which result in the INR changing for the same daily dose. Also consider the idea that one can find a comfortable dose

which fits within a safe range. However (as identified in that article) its possible that the natural variations may take you outside of the zone ideal zone. Naturally regular testing makes it clearer what is happening and helps you stay within range (

a good thing).

At the end of the day one could take the view that I could have just sat on a dose of 7.5mg per day and been done with it. However its clear from the data that there were times when I'd have had an INR of probably close to 4 or perhaps more. If I had allowed that to happen it would actually be risky in terms of a bleed event (

perhaps even provoked by a fall off my mountain bike).

So to me the answer is frequent monitoring.

Since the cost of a test is quite low I really don't mind making extra tests per year than work with some "theoretical minimum". I believe its always good to have more information than not enough. In fact not enough data leads to you not being able to understand why you had the problem.

I think that its perhaps a good time to talk about my little problem: I'm over analytical. Probably I record more data than is needed. Some people don't record as much as me or even do any analysis. Hell even I'm willing to concede that most of what I keep is only of benefit when making analysis. My Coaguchek XS stores the last 100 or so readings anyway, so if I wanted to skip back through that it shows the INR and the date.

However its no harder to keep a month of readings and graph it than it is to keep all of it. I keep my records rigorously in a spread sheet (which is backed up onto dropbox for just in case) and use that data to form the basis of my analysis and learning about myself.

If nothing else it has given me knowledge and has removed the anxiety of "oh sheet, I missed a dose" ... and knowing if this is a problem or not.

Understand that your body is not a static thing and that things such as starting a new sport, stopping a sport or change of diet will alter your metabolism and you'll need to check your INR. Since you're checking weekly (

see my above point on frequent monitoring) you'll pick it up quick smart anyway.

If reading this has helped you to understand that change a bit more then that's a good thing too :-)

Food

Have you noticed that I haven't talked about food? Well the reason is that I've found that it makes stuff all difference (unless you eat a whole case of spinach in a sitting) and if you did start get any change to your INR you'd see that in the next weeks measurement :-) If you do see anything, work out if this is important and if its actually a consistent diet change.

BTW I don't do fad diets. Instead I more or less watch what I eat ... almost all the way to my mouth so as not to get it on my shirt.

So, in short, don't stress, be happy, keep a weather eye on the horizon and a steady hand on the tiller. Make course corrections only when you are sure they're needed ...

Hopefully all this has helped you become a better navigator of your INR

Live Long and Prosper